- Founder, Work of the People and Working, International, a collaborative design and development studio, research art practice, and publishing imprint

- VP, Design, MasterClass

- Founding member, fmr. Chief Creative Officer, Head of Design & NYC Studio at VSCO and PLAZA, a VSCO product and design lab exploring AI and decentralized spaces for ideas and exchange

- Co-Founder, Table, a record of contemporary Asian and Pacific Islander creativity

- Independent study at The New School

- Contextually changing omni-directional navigation mechanism US9977569B

- Recon, or, surveillance architecture

- Ephemera, comments on sedimentation

- some links: cv, are.na, instagram, vsco, substack

- wayne@workofthepeople.co

EPHEMERA

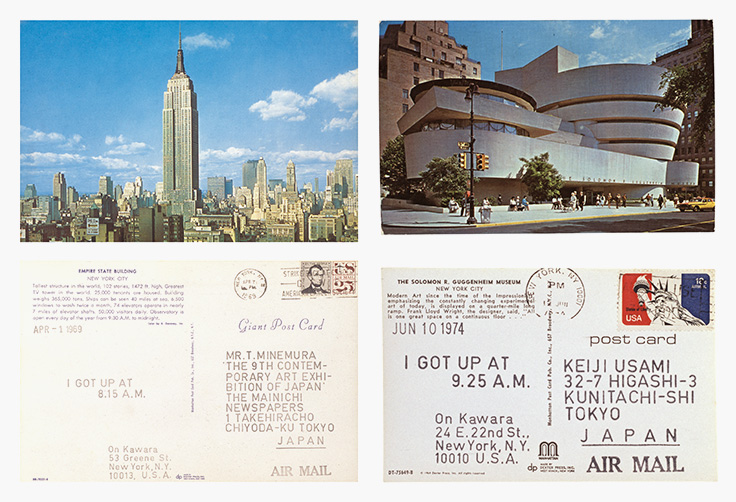

Two other 20th century conceptualists employ a similar conceit in their practice. In 1969, On Kawara created I Went, I Met, I Read, a four volume journal in which Kawara documented every personal journey, human encounter and newspaper article he encountered during that year into a single journal. (Fig. 2) Of course, Kawara is most well known for his date paintings in which a painting of the date would need to be completed within the same day and within such constraints an observer might see the slight variances that the daily events of the world may affect on the painter. For Kawara, “[time]...is...the small, daily accretions, the repetitions, the barely-there variation in daily routine, and the quiet, at times breathtaking, pronouncements comprised of simple action verbs: I got up; I went; I met; I read...I Am Still Alive.” [2]

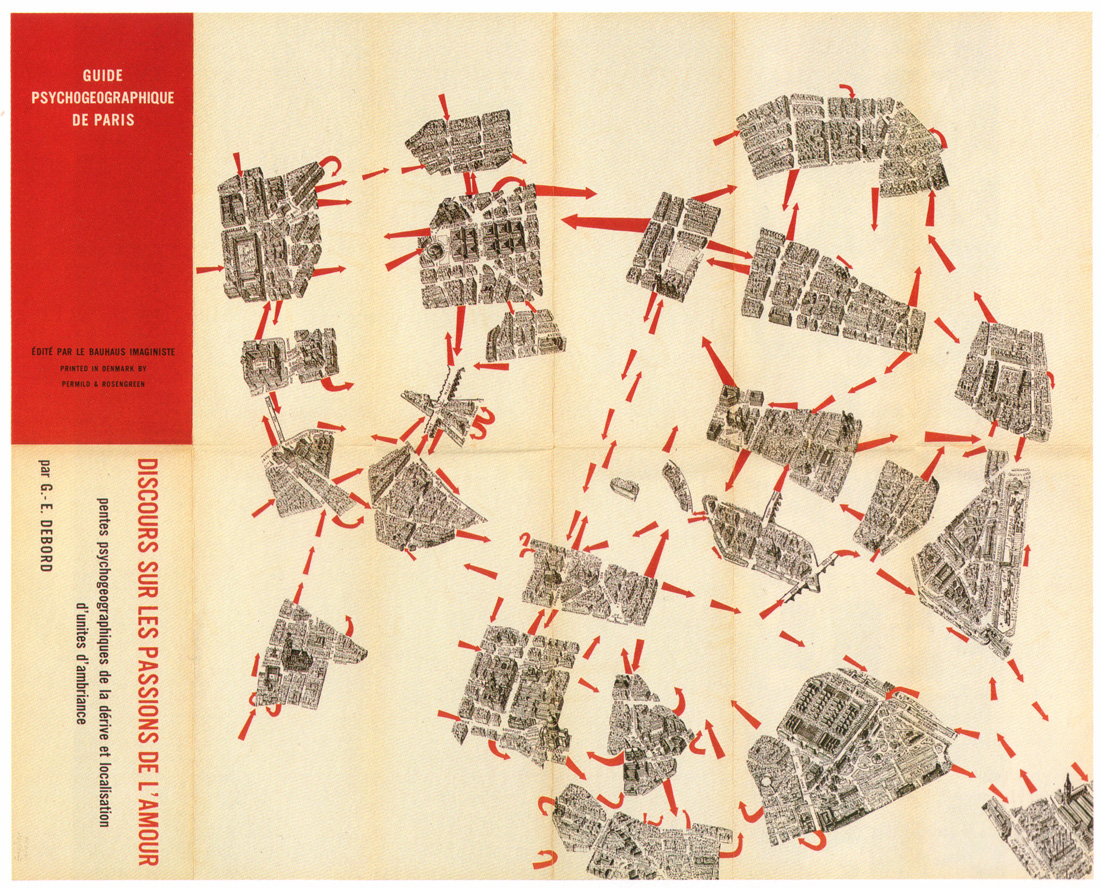

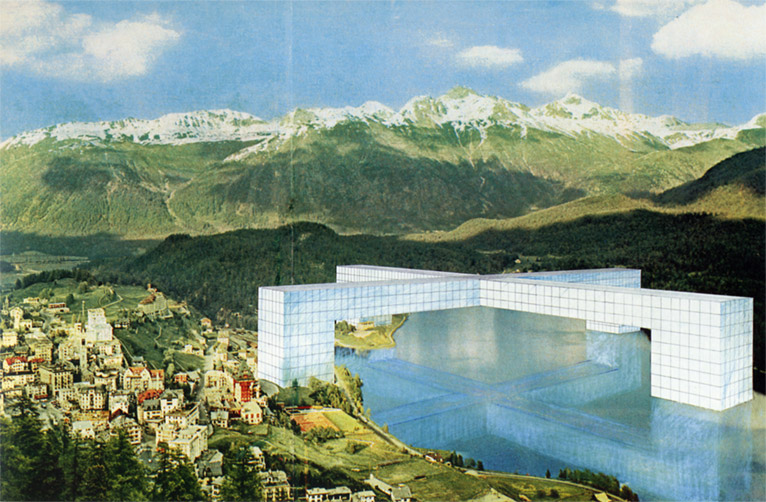

This documentary-like work of Broodthaers, Kawara and Darboven, among others, inform a particular personal practice developed over many years. Depending on key inputs, specific rituals are developed as tools of examination. In the case of "Ephemera", daily half-hour sessions, called excavations, were employed. Each session was centered around exploring the catalysts of creation, mutation, and metamorphosis by exploring society, nature and the human problem as it is, where it has been, and where it could be. What would a “post-human” - that is to say, not void of humanity, but humanity’s metamorphosis, look like? The only rule of each excavation was to allow the documentarian to be divergent, to be open to the infinite, to be rhythmic, to be incomplete, and to suspend analysis in the spirit of dérive.

“Ephemera” is a survey of collected materials gathered through these daily rituals: a series of documents that simply offer departures from the collected detritus. These initial three entries explore thoughts around geological sediment, atmospheric dust, and their extraterrestrial counterpart, the meteorite. Moving forwards, the mandate for “Ephemera” is to grow towards an extrospective versus introspective response, from observation to participation and performance, from self-indulgence to generosity.

01

Sediment

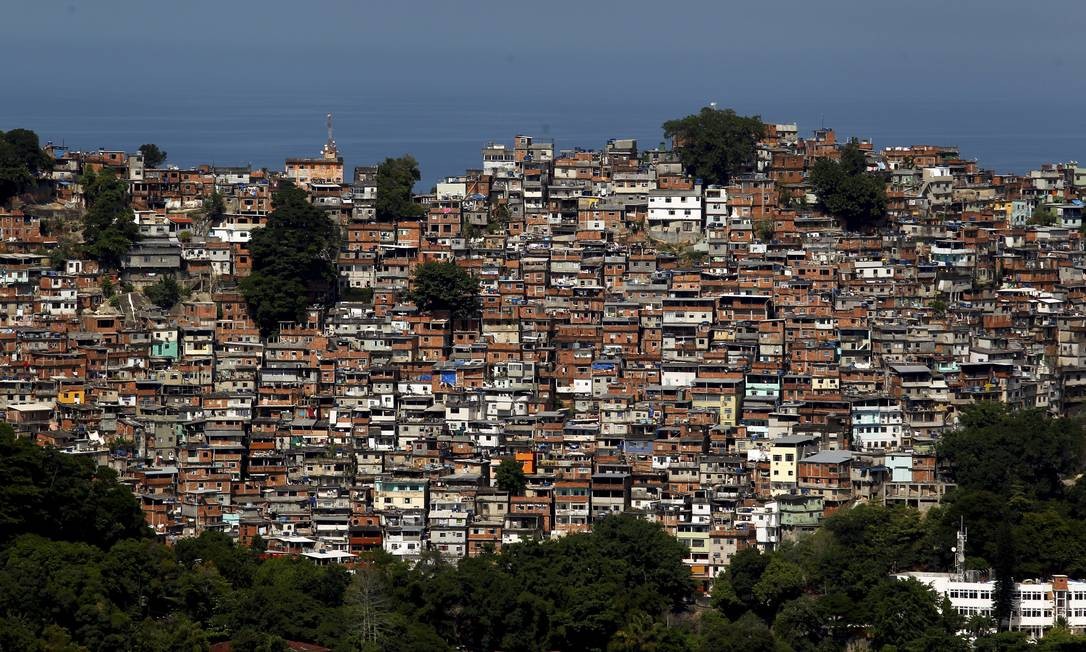

It is, apparently, a documented misconception that the city of Vancouver is located on Vancouver Island, when it is in fact located on the Burrard peninsula, bounded by the Fraser river to its south and the Burrard Inlet to its north. Vancouver Island does exist however — formed by an oceanic rift that resulted in a volcanic accretion that rammed into the western edge of the North America some time ago. Separating the island from the city is a body of water called the Strait of Georgia, in which over two hundred smaller islands (collectively known as the Gulf Islands), inhabit, and into which the Fraser river thrusts millions of tons of sediment each year. [4] (Fig. 4) While Vancouver Island’s material composition, as would be expected given its origin, contains volcanic rock, it is also composed of sedimentary rock, which is often formed from the accumulation of small, “pre- existing rocks or pieces of once living organisms” [5] via a unique mixture of sources and transport processes, both natural and artificial. In aggregate, over time, they become concretized and compacted into layers, or strata, in which time, and thus history, become archive. Geologists study them as a person would a history book, slicing them with a knife and inferring truth about the past to inevitably explain the present, and predict the future: a genealogy of sorts. Yet in its present space and time, sedimentation is active, fluid, energetic, violent, creative, and transient - more rhizome than binary root. Each particle, billions among billions, is shaped differently, composed of mixtures of both natural and artificial compounds, sourced from distances far and near, carried by ice, water, rain, wind and other means; some at such slow velocities they seem as if they are not moving at all, and others as fast as the wind or water can carry them. Many particles dissolve in this mad swirl, while others aggregate, succumb to gravity, and settle: forming new spaces, pockets and islands that become primordial grounds for creation, disruption, destruction, illusion and imagination (Fig. 5, 6). If a casual weekend geologist could witness this phenomenon, he or she may determine that the swirl looks rather angry, in the Bachelardian sense. [6]

Perhaps the nature of our being exists in this suspension between the strata of our history and the present moment and all of its entrances and exits that we are taken through, by our own “free will” or not. This suggestion is a sort of “both-and” existence: we are swimming in both the concrete, compacted sludge of our histories that have fossilized over time, and the present angry swirl. In the geologic context, this is observable. It is empirical truth. The delicate balance between violence, destruction, stress, displacement and creation, biodiversification, regeneration can be simply understood as the natural order of the world. In the human context, however, this becomes rather problematic.

The first problem arises in the nature of the concrete sediment itself. Sedimentary rock is a compaction of sediment, a compositional artifact or photograph of a period of angry swirl: perhaps a hundred years, or a thousand years. Canonized within its structure are the remnants and monuments of a violent era of creation and destruction. However, what is not conveyed within the layers are the details: the currents, the speed, the “philosophy of the middle.” In other words, the concretized sediment lacks the full dataset. This problem is further compounded by the geologist, or the interpreter, who can only extract an even smaller dataset at a given time. The consequence, then, is an understanding of the world that can be severely compromised.

How then, should we navigate, if at all? The 20th century land-art pioneer, Robert Smithson, along with his contemporaries, Walter de Maria and Michael Heizer, offer a possible way forward.

In the September 1968 issue of Artforum, Smithson, in a feature entitled “A Sedimentation of the Mind” wrote: “The strata of the Earth is a jumbled museum. Embedded in the sediment is a text that contains limits and boundaries which evade the rational order, and social structures which confine art. In order to read the rocks we must become conscious of geologic time, and of the layers of prehistoric material that is entombed in the Earth’s crust. When one scans the ruined sites of prehistory one sees a heap of wrecked maps that upsets our present art historical limits. A rubble of logic confronts the viewer as he looks into the levels of the sedimentations. The abstract grids containing the raw matter are observed as something incomplete, broken and shattered.” In it he recounts a time where he visits a quarry in which he felt like he had “fallen into endless directions of steepness” as he “gaz[ed] on countless stratographic horizons.” He concludes: “How can one contain this ‘oceanic’ site? I have developed the Non-Site, which in a physical way contains the disruption of the site. The container is in a sense a fragment itself, something that could be called a three- dimensional map. Without appeal to “gestalts” or “anti-form,” it actually exists as a fragment of a greater fragmentation. It is a three dimensional perspective that has broken away from the whole, while containing the lack of its own containment. There are no mysteries in these vestiges, no traces of an end or a beginning.” [13]

“‘Cerberus’ is an exhibition dedicated to places difficult and in- between, where conflicts arise, but also where the hope of resolution is to be found. Fundamental to these works is a process of layering. Just as the very fabric of each painting is formed from strata of pigmented paper which are scored, lacerated and stripped away, Bradford collides a multiplicity of references. The longer timeline of myth-making combines with events from more recent history and a trajectory of painting from the Hudson River School to Robert Rauschenberg via Asger Jorn...As Bradford explains, ‘I have always been interested in pulling the world that exists beyond the studio walls, and outside the art world, into the work.’ The titles ‘Cerberus’ and ‘Gatekeeper’ (2019) make metaphorical reference to notions of containment, of pressure building to an incendiary point, and also the idea of a border as a juncture or gathering place.” [14]

02 Dust

Whereupon sediment erupts into the atmosphere.

The smallest particles within the classification of volcanic tephra is generally known as fine volcanic ash, or volcanic dust. In the case where the finest of this dust reaches heights in excess of 40km during an eruption event — well into the upper reaches of the stratosphere — the dust can stay resident for as long as two decades and move for thousands of kilometers in any direction (Fig. 16). Depending on the individual particle size, eruption height, mobility vectors such as wind, and the overall density of the eruption, such events create observable phenomena. [16]

Human inclination is to search for such a synthesis of cause-effect, serialized into a historical narrative. The world experienced climate change because of a volcanic eruption, leading to change in global agricultural harvests, leading to regional food shortages, and so on. In every situation, the tendency of the mind is to organize, synthesize, and reach for conclusion. The unfortunate outcome of such patterns of thought is the creation of half-baked ideologies that separate and dismiss, sometimes to catastrophic effect.

The alternative is to consider the “island” as a singleton - a cellular automaton; and the “archipelago” as Turing machine. The life of the island is the genesis of climate. Each piece of microscopic dust is an island that contains within itself a microclimate — a dream where orders of scale, distance, and time are reconfigured. Such spaces require the full extent of inquiry, patience, study and dialogue. Every corner must be explored: the vectors that cause them to migrate over great distances, the textures of its landscape, its color palette, how time, gravity, sound, and temperature function, and so on. The dust should be understood as a liminal space - adrift in transition and disorientation, where time seems to fold on itself. It is within the knowledge of the single dust, that harmonies and dischords can be perceived between fellow specks of dust, and in which the larger atmospheric identity (the archipelago) and its effect can be discerned.

Two years later, in 1958, composer John Cage premiered “Concert for Piano and Orchestra,” where the composition can be played “in whole or in part, in any sequence...in any duration, with any number of...performers.” [19] Of primary importance was for it to be played by the musician as an island of sorts, within the rules of the instrumentation, but all other dynamics such as time, particular instrument, amplitude, and so on at the interpretation of the artist. In other words, every performance of the concert was unique, adrift, slowly falling from the atmosphere at its own pace, according to the winds of the moment, where time, shape, texture and color were defined in real time.

The result was that every performance was notated as a particular variation, allowing for an infinite number of islands. Taken together, a topography is created: an archipelagic symphony. (Fig. 19)

If we are to discover the possibility of new narratives, then the 21st century imperative for humanity is to consider that the collective atmosphere, or climate, in which we inhabit, is a symphony. Our fellow neighbor, a speck of dust adrift among seven billion, possesses a microclimate that is infinite in space and time that is worth exploring with utmost patience and consideration; for we are all dust.

“As one dies, so dies the other. All have the same breath...All go to the same place; all come from dust, and to dust all return.” — Ecclesiastes 3:19-20

03

Meteorite

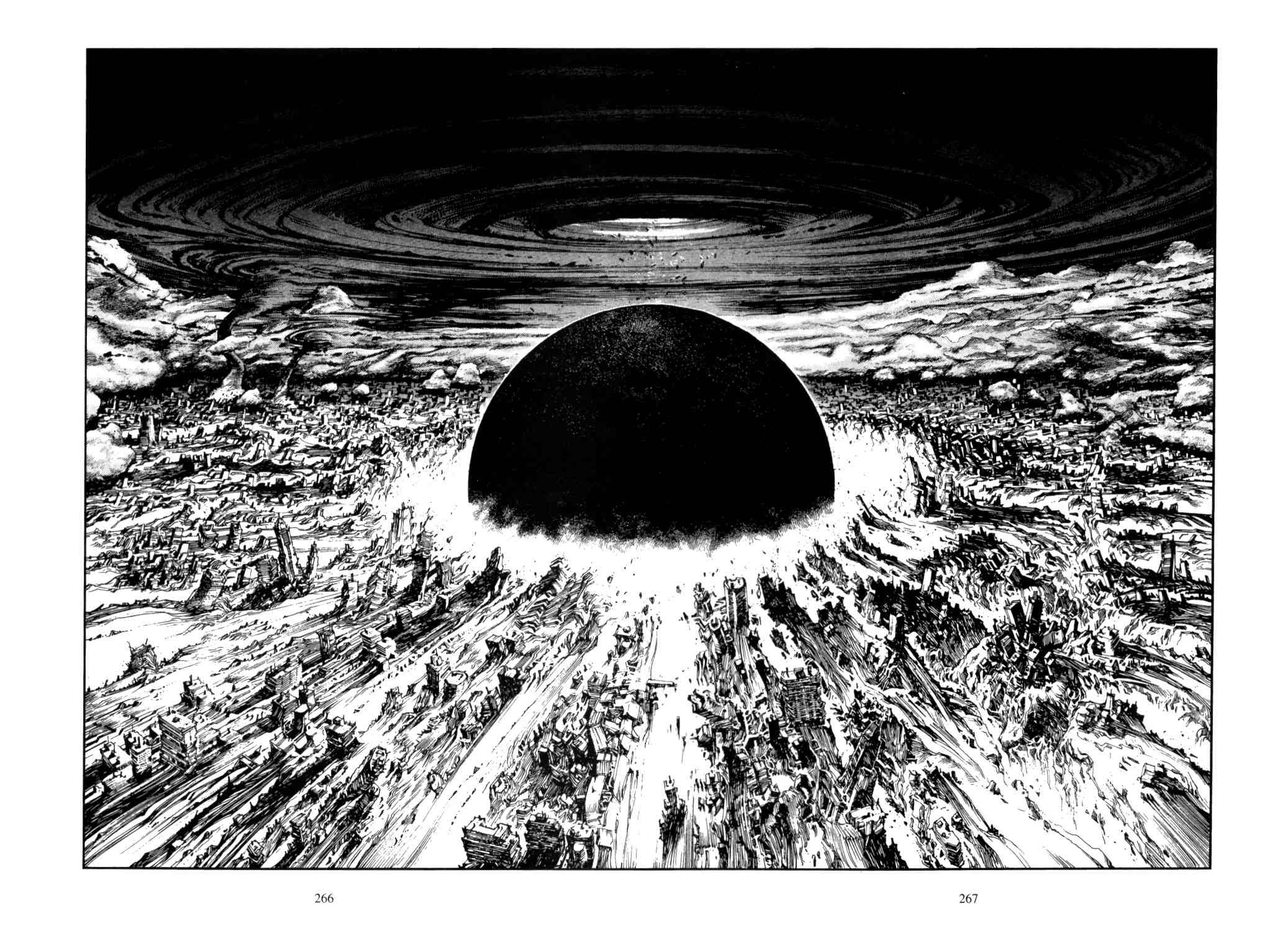

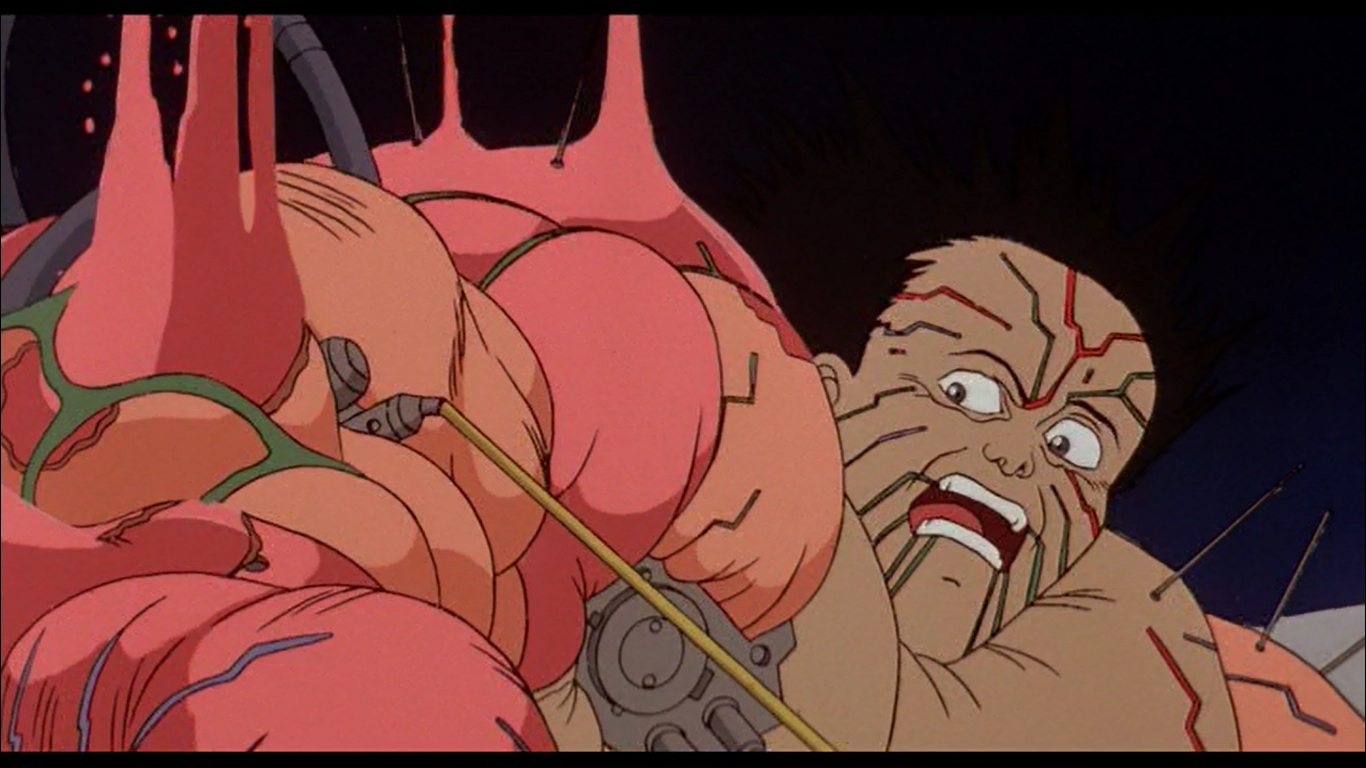

The past decade, however, is witness to a series of scientific studies that speak of the creative, or life-giving, potential of extraterrestrial matter that regularly penetrates the Earth’s atmosphere. In 2014, scientists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison proved that plants could grow both in microgravity and within simulated lunar and Martian soil, which is very similar in material composition to volcanic soil from Earth. [25] In 2015, the NASA Ames Research Center reproduced the basic building blocks of RNA and DNA by simulating conditions in outer space. [26] Subsequently, in 2018, scientists from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found an “extensive” variety of organics – viewed as direct evidence of complex prebiotic chemistry – in two meteorites found in 1998 named Zag and Monahans. [27] More recently, an international group of astrobiologists led by Yoshihiro Furukawa of Tohoku University, Japan, discovered a series of “bio- essential” sugars in two carbon-rich meteorites named NWA 801 and Murchison. These sugars, specifically ribose and deoxyribose, are essential to the formation of biopolymers that are the basis for life, and the evidence of their existence in extraterrestrial form suggest that at least part of earth’s biodiversity may be of foreign origin. [28]

Similarly, microbiologists have shown that meteorites arrive in a particular ecology in a sterile form that is alien to its local environment can introduce a bacterial distribution change in the soil due to its abundance in energy generating material, thus creating variability to the microbiology of its locale. [29] A terrestrial analogue to this can be found in the ecology of beaver dams. When a beaver population moves into a new territory (foreign invasion), they build dams that alter the movement of water and create systemic changes to the local ecosystems from flora to fauna. On one hand, this invasive species can be viewed as colonizers, and on the other hand they may be viewed as generators of biodiversity, and both perspectives would be true. For one set of species, their appearance is tantamount to the apocalypse, and for another, biogenesis and biodiversity. [30]

- Dirk Snauwaert, “Marcel Broodthaers, “Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, Section des Figures,” 1972 – THE ARTIST AS CURATOR #5” Mousse, last modified August 26, 2015, http://moussemagazine.it/taac5-a/

- Matin Momen, “On Kawara - Silence,” StyleZeitgeist, last modified February 10, 2015, https://www.sz-mag.com/news/2015/02/on-kawara-silence/

- Jason Farago, “The Perils of Order, Taken to the Extreme,” New York Times, last modified December 8, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/08/arts/design/ hanna-darboven-kulturgeschichte.html

- Cannings, Richard and Sidney. British Columbia: A Natural History. p.41. Greystone Books. Vancouver. 1996

- What are Sedimentary Rocks” US Geological Survey, USGS, https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/what-are-sedimentary-rocks-0

- ‘The imagination, for which the mill prepared the way, spreads out across the universe: these whirlwinds, says Blake, are “starry voids of night & the depths & caverns of earth.” ... We do not perceive the cosmogonic whirlwind, the creative tempest or the wind of anger and creation in their geometrical forms, but rather as sources of power. Nothing can stop the whirling motion. In dynamic imagination, everything becomes active; nothing comes to rest. Motion creates being; whirling air creates the stars; the cy produces images, speech, and thought. As by a provocation, the world is created through anger. Anger lys the foundations for dynamic being. Anger is the act by which being begins. However prudent an action may be and however insidious it promises to be, it must first cross over a small threshold of anger. Anger is the acid without which no impression will be etched on our being. It creates an active impression.’ Bachelard, Gaston. Air and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Movement. p. 227. Dallas Institute Publications. Dallas, Texas. 1988.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. p.131. Routledge, 2012, 2014. New York.

- Merleau-Ponty, op. cit., p. 132

- Baker, Aylie. “Wave Patterns.” https://emergencemagazine.org/story/wave- patterns/

- Baker, op. cit.

- Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. p. 47. University of Michigan Press. Ann Arbor. 1997

- Glissant, op. cit., p. 7

- Smithson, Robert. “A Sedimentation of the Mind.” Artforum. Sept. 1968. pp 82- 91.

- Hauser and Wirth, https://www.hauserwirth.com/hauser-wirth- exhibitions/25237-mark-bradford-cerberus

- Sloterdijk, Peter. Stress and Freedom. pp. 54-55. Polity Press. Cambridge, UK 2016

- “Residence times of 10-20 years are clearly possible for non-spherical volcanic fragments of dimensions about the wavelength of maximum solar energy around 0.5um, and possibly up to 10 years for many of the fragments of 0.5 to 1um size; though poleward transport might mean that such long residence times effectively occur only over the polar regions, if anywhere.” Lamb, H. H. “Volcanic Dust in the Atmosphere; with a Chronology and Assessment of Its Meteorological Significance.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, vol. 266, no. 1178, 1970, pp. 425–533. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/73764.

- “The Bishop’s Ring that was observed in the August 1883 eruption of Krakatau was seen 2.8 years later in Europe, 3.1 years later in Colorado, and in the subtropical latitudes 1-1.3 years, where the tropopause is sometimes as high as 15-17km.” Lamb, H. H. “Volcanic Dust in the Atmosphere; with a Chronology and Assessment of Its Meteorological Significance.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, vol. 266, no. 1178, 1970, pp. 425–533. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/73764.

- Conway, Erik. “The Year Without a Summer.” Ask NASA Climate. Nasa Jet Propulsion Laboratory. https://climate.nasa.gov/blog/183/

- Cage, John. “Concert for Piano and Orchestra.” Peters Edition EP 6705, EP 6705a-m, EP 6705n. https://johncage.org/pp/John-Cage-Work-Detail.cfm?work_ ID=48

- Kawakubo has professed to working in a manner that mimics Woolf’s stream of consciousness, allowing this ‘madness’ to shape her expression, rather than attempting to create a means by which it can be expressed. “My approach is simple,” she says to Interview Magazine’s Ronnie Cooke Newhouse. “It is nothing other than what I am thinking at the time I make each piece of clothing, whether I think it is strong and beautiful. Seward, Maharo. “Rei Kawakubo: Writing the Fashion of Madness.” 1 Granary. https://1granary.com/fashion-journalism/rei-kawakubo-writing-the-fashion- of-madness/

- Zhang Ga. “Datumsoria: The Return of the Real.” Weight of Insomnia: Liu Xiaodong. Lisson Gallery.

- With the single literal assertion of the “island-as-void,” the accepted preservationist hierarchies between exterior and interior, and mass and surface were undermined. Indeed with the metaphorical embrace of the void, the island’s status as a site of mystery, projection, and fantasy became the most critical aspect to preserve over its mere material presence. Andraos, Amale. “New Holland Island: Strategies of the Void.” Perspecta 48. The Yale Architectural Journal. MIT Press. 2105. pp. 202-209.

- Andraos, Amale. “New Holland Island: Strategies of the Void.” Perspecta 48. The Yale Architectural Journal. MIT Press. 2105. pp. 202-209.

- Gerrit L. Verschuur, Impact! - The Threat of Comets and Asteroids, (Oxford University Press, 1998), 116.

- Michael Slezak, “Asteroid soil could fertilise farms in space,” The New Scientist, last modified December 16, 2014, https://www.newscientist.com/article/ mg22430004-900-asteroid-soil-could-fertilise-farms-in-space/

- Ruth Marlaire, “NASA Ames Reproduces the Building Blocks of Life in Laboratory,” NASA.gov, last modified August 7, 2017, https://www.nasa.gov/content/ nasa-ames-reproduces-the-building-blocks-of-life-in-laboratory

- Queenie H. S. Chan, Michael E. Zolensky, Yoko Kebukawa, Marc Fries, Motoo Ito, Andrew Steele, Zia Rahman, Aiko Nakato, A. L. David Kilcoyne, Hiroki Suga, Yoshio Takahashi, Yasuo Takeichi and Kazuhiko Mase, “Organic matter in extraterrestrial water-bearing salt crystals,” Science Advances, vol. 4, no. 1 (January 2018), https:// advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/1/eaao3521

- Bill Steigerwald, Nancy Jones, “First Detection of Sugars in Meteorites Gives Clues to Origin of Life,” NASA.gov, last modified November 20, 2019, https://www. nasa.gov/press-release/goddard/2019/sugars-in-meteorites

- Alastair W. Tait, Emma J. Gagen, Siobhan A. Wilson, Andrew G. Tomkins, and Gordon Southam, “Microbial Populations of Stony Meteorites: Substrate Controls on First Colonizers,” Frontiers in Microbiology., vol. 8 1227 (June 30, 2017), https://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5492697/

- Paul D. Haemig, “Ecology of the Beaver,” Ecology.Info, no. 13 (2012), http:// www.ecology.info/beaver-ecology.htm

- Ees, “Akira: An Analysis of the A-Bomb and Japanese Animation,” The Artifice, https://the-artifice.com/akira-analysis/

- Henri Lefebvre, Introduction to Modernity, (Verso, 2012), 129.

- Leopold Lambert, “The Political Archipelago: For a New Paradigm of Territorial Sovereignty,” The Funambulist, https://thefunambulist.net/history/politics-the- political-archipelago-for-a-new-paradigm-of-territorial-sovereignty

- Stephen Wallis, “A ’60s Architecture Collective That Made History (but No Buildings)“, The New York Times, Last Updated April 13, 2016, https://www.nytimes. com/2016/04/04/t-magazine/design/superstudio-design-architecture-group-italy. html

- Ian Cheng, “Worlding Raga: 2 — What is a World?” Ribbonfarm, last modified March 5, 2019, https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2019/03/05/worlding-raga-2-what-is-a- world/

- Stuart Comer, Ian Cheng, “Ian Cheng’s Emissaries,” MoMA.org, last modified March 6, 2019, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/40?utm_ source=social&utm_medium=bitly&utm_campaign=Magazine&utm_ content=newtomoma_iancheng

- Sou Fujimoto, “House N / Sou Fujimoto Architects,” Arch Daily, last modified September 14, 2011, https://www.archdaily.com/7484/house-n-sou-fujimoto